The ultra-pure icicle is pictured on the left, and the water droplet on the right.

Credit: TU Wien

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then this is one divine droplet.

As you may know from scrubbing the kitchen, getting a surface well and truly clean is a real challenge – and even more so for scientists working at microscopic levels.

No matter how pristine a material is engineered to be, it always ends up covered in a thin layer of molecules.

Now new research has produced the cleanest water droplets ever created in an attempt to figure out why it's so hard to create perfect self-cleaning surfaces.

One hypothesis was that this layer of molecular dirt comes from water.

To investigate, researchers used pure ice frozen in a vacuum chamber to produce water droplets completely free of dirt and defects, and then dropped the liquid onto pristine surfaces made from titanium dioxide, known for its self-cleaning properties.

What they found was that the layer of molecular dirt that's attracted to ultra-clean surfaces isn't actually water, as previously believed. It's actually something much more surprising.

This 'dirt' is made up of two organic acids, acetic acid (which adds to the sourness of vinegar) and formic acid, which is closely related.

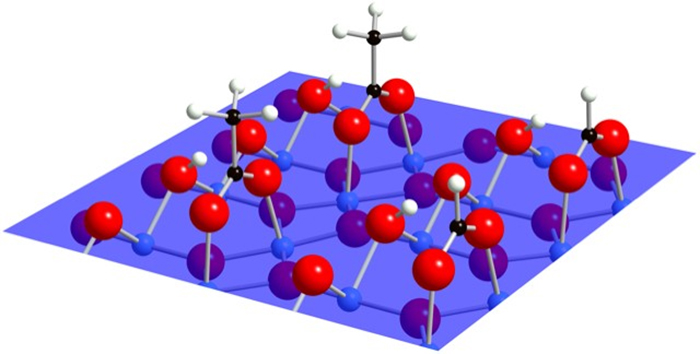

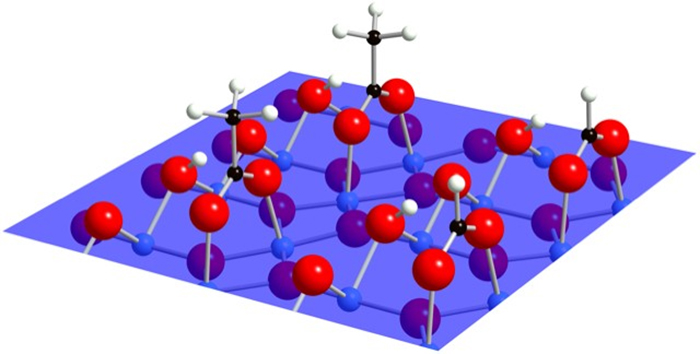

Graphic simulation of molecular layer. (Cornell University)

Graphic simulation of molecular layer. (Cornell University)

That's a surprising finding, considering these acids are only found in very low quantities in normal air.

It could prompt a rethink on how surfaces attract and repel dirt, and even how future studies could ensure surfaces that are completely, spotlessly clean.

Even creating clean water was a challenge.

"In order to avoid impurities, experiments like these have to be carried out in a vacuum," says one of the team, Ulrike Diebold from the Vienna University of Technology in Austria.

"Therefore, we had to create a water drop that never came into contact with the air, then place the drop on a titanium dioxide surface that had been scrupulously cleaned down to the atomic scale."

The extra dirt layer – a single layer of molecules thick – only appeared when the titanium dioxide surface was taken out of the vacuum and exposed to the air. So it wasn't the water making it dirty.

This explains why titanium dioxide, which is used in everything from car mirrors to building tiles, always attracts this extra layer, even after using the Sun's energy to burn off most of the material that collects on top of it.

"Somehow these molecules on the surface are helping with this really interesting chemistry, the self-cleaning and oxidising properties," says one of the researchers, Melissa Hines from Cornell University in New York.

"And we're just beginning to understand what's going on there."

The scientists think that a special bidentate (or "two teeth") binding happening at the chemical level helps the acids stick to the titanium dioxide, even though there are only a few parts-per-billion of these particles in air.

Other molecules that are much more common in air slip or wash right off the surface because they don't have the same kind of binding mechanism.

To make sure they had their results right, the researchers tested the process of applying ultra-clean water droplets to titanium oxide in both the United States and Austria.

"It was crucial that we do the experiment in more than one place," says Hines. "If we had just done it in Vienna, everyone would say, 'For some reason, your building is full of vinegar.'"

There's still a lot to unpack and investigate here, the researchers admit, but it's a significant finding in helping us understand why these surfaces can't get completely clean when they're exposed to air.

At the same time, it explains how titanium dioxide can repel almost all other molecules – because of the acid it attracts.

"This result shows us how careful we need to be when conducting experiments of this kind," says Ulrike Diebold. "Even tiny traces in the air, which could actually be considered insignificant, are sometimes decisive.

Researchers at the Vienna University of Technology announced yesterday (Aug. 23) that they have created the cleanest drop of water in the world.

This ultrapure water could help explain how self-cleaning surfaces, such as those coated with titanium dioxide (TiO2), become covered with a mysterious layer of molecules when they come into contact with air and water.

"We had four labs [around the world] studying this and four different explanations for it," said study co-author Ulrike Diebold, a chemist at the Vienna University of Technology.

But leave them in a dark room too long, Diebold said, and the mysterious dirt forms.

Most of the proposed explanations for this involve some sort of chemical reaction with ambient water vapor. But Diebold and her colleagues applied the ultraclean water droplet to the surface and showed that water alone doesn't cause the film to appear.

Creating that superclean drop was a challenge, though. As Live Science previously reported, water very easily becomes contaminated with trace impurities, and perfectly pure water does not exist.

To get as close to perfectly pure as possible, Diebold said, her team had to design a specialized gadget that pushed water to its limits.

In one chamber of the device was a vacuum, with a "finger" hanging from its ceiling cooled to minus 220 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 140 Celsius). The researchers then released a thin, purified sample of water vapor from an adjacent chamber into the vacuum, so that the water formed an icicle at the tip of that finger. The researchers then allowed the icicle to warm up and melt, so that it dripped onto a piece of TiO2 below before quickly evaporating into the ultra-low-pressure chamber. Afterward, the TiO2 showed no sign of the molecular film that some researchers suspected came from water, the researchers reported today (Aug. 23) in the journal Science.

"The key is that neither the water nor the titanium dioxide had ever been exposed to air before," Diebold said.

Follow-up scans of TiO2 using microscopes and spectroscopes showed that the film wasn't made up of water or water-related compounds at all. Instead, acetic acid (which gives vinegar its sour taste) and formic acid, a similar compound, turned up on the surface. Both are byproducts of plant growth and are present in only tiny quantities in the air — but, apparently, there's enough of this material floating around to dirty a self-cleaning surface.

Credit: TU Wien

If cleanliness is next to godliness, then this is one divine droplet.

As you may know from scrubbing the kitchen, getting a surface well and truly clean is a real challenge – and even more so for scientists working at microscopic levels.

No matter how pristine a material is engineered to be, it always ends up covered in a thin layer of molecules.

Now new research has produced the cleanest water droplets ever created in an attempt to figure out why it's so hard to create perfect self-cleaning surfaces.

One hypothesis was that this layer of molecular dirt comes from water.

To investigate, researchers used pure ice frozen in a vacuum chamber to produce water droplets completely free of dirt and defects, and then dropped the liquid onto pristine surfaces made from titanium dioxide, known for its self-cleaning properties.

What they found was that the layer of molecular dirt that's attracted to ultra-clean surfaces isn't actually water, as previously believed. It's actually something much more surprising.

This 'dirt' is made up of two organic acids, acetic acid (which adds to the sourness of vinegar) and formic acid, which is closely related.

Graphic simulation of molecular layer. (Cornell University)

Graphic simulation of molecular layer. (Cornell University)That's a surprising finding, considering these acids are only found in very low quantities in normal air.

It could prompt a rethink on how surfaces attract and repel dirt, and even how future studies could ensure surfaces that are completely, spotlessly clean.

Even creating clean water was a challenge.

"In order to avoid impurities, experiments like these have to be carried out in a vacuum," says one of the team, Ulrike Diebold from the Vienna University of Technology in Austria.

"Therefore, we had to create a water drop that never came into contact with the air, then place the drop on a titanium dioxide surface that had been scrupulously cleaned down to the atomic scale."

The extra dirt layer – a single layer of molecules thick – only appeared when the titanium dioxide surface was taken out of the vacuum and exposed to the air. So it wasn't the water making it dirty.

This explains why titanium dioxide, which is used in everything from car mirrors to building tiles, always attracts this extra layer, even after using the Sun's energy to burn off most of the material that collects on top of it.

"Somehow these molecules on the surface are helping with this really interesting chemistry, the self-cleaning and oxidising properties," says one of the researchers, Melissa Hines from Cornell University in New York.

"And we're just beginning to understand what's going on there."

The scientists think that a special bidentate (or "two teeth") binding happening at the chemical level helps the acids stick to the titanium dioxide, even though there are only a few parts-per-billion of these particles in air.

Other molecules that are much more common in air slip or wash right off the surface because they don't have the same kind of binding mechanism.

To make sure they had their results right, the researchers tested the process of applying ultra-clean water droplets to titanium oxide in both the United States and Austria.

"It was crucial that we do the experiment in more than one place," says Hines. "If we had just done it in Vienna, everyone would say, 'For some reason, your building is full of vinegar.'"

There's still a lot to unpack and investigate here, the researchers admit, but it's a significant finding in helping us understand why these surfaces can't get completely clean when they're exposed to air.

At the same time, it explains how titanium dioxide can repel almost all other molecules – because of the acid it attracts.

"This result shows us how careful we need to be when conducting experiments of this kind," says Ulrike Diebold. "Even tiny traces in the air, which could actually be considered insignificant, are sometimes decisive.

Researchers at the Vienna University of Technology announced yesterday (Aug. 23) that they have created the cleanest drop of water in the world.

This ultrapure water could help explain how self-cleaning surfaces, such as those coated with titanium dioxide (TiO2), become covered with a mysterious layer of molecules when they come into contact with air and water.

"We had four labs [around the world] studying this and four different explanations for it," said study co-author Ulrike Diebold, a chemist at the Vienna University of Technology.

In the light of day

When TiO2 surfaces are exposed to ultraviolet light, they react in ways that "eat up" any organic compounds on them, Diebold told Live Science. This gives these surfaces a number of useful properties; for example, a TiO2-coated mirror will repel water vapor even in a steamy bathroom.But leave them in a dark room too long, Diebold said, and the mysterious dirt forms.

Most of the proposed explanations for this involve some sort of chemical reaction with ambient water vapor. But Diebold and her colleagues applied the ultraclean water droplet to the surface and showed that water alone doesn't cause the film to appear.

Creating that superclean drop was a challenge, though. As Live Science previously reported, water very easily becomes contaminated with trace impurities, and perfectly pure water does not exist.

To get as close to perfectly pure as possible, Diebold said, her team had to design a specialized gadget that pushed water to its limits.

In one chamber of the device was a vacuum, with a "finger" hanging from its ceiling cooled to minus 220 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 140 Celsius). The researchers then released a thin, purified sample of water vapor from an adjacent chamber into the vacuum, so that the water formed an icicle at the tip of that finger. The researchers then allowed the icicle to warm up and melt, so that it dripped onto a piece of TiO2 below before quickly evaporating into the ultra-low-pressure chamber. Afterward, the TiO2 showed no sign of the molecular film that some researchers suspected came from water, the researchers reported today (Aug. 23) in the journal Science.

"The key is that neither the water nor the titanium dioxide had ever been exposed to air before," Diebold said.

Follow-up scans of TiO2 using microscopes and spectroscopes showed that the film wasn't made up of water or water-related compounds at all. Instead, acetic acid (which gives vinegar its sour taste) and formic acid, a similar compound, turned up on the surface. Both are byproducts of plant growth and are present in only tiny quantities in the air — but, apparently, there's enough of this material floating around to dirty a self-cleaning surface.

0 comments: