Patient education: Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) in diabetes mellitus (Beyond the Basics)

LOW BLOOD SUGAR OVERVIEW

Hypoglycemia, also known as low blood sugar, occurs when levels of glucose (sugar) in the blood are too low. Hypoglycemia is common in people with diabetes who take insulin and some (but not all) oral diabetes medications.

WHY DO I GET LOW BLOOD SUGAR?

Low blood sugar happens when a person with diabetes does one or more of the following:

●Takes too much insulin (or an oral diabetes medication that causes your body to secrete insulin)

●Does not eat enough food

●Exercises vigorously without eating a snack or decreasing the dose of insulin beforehand

●Waits too long between meals

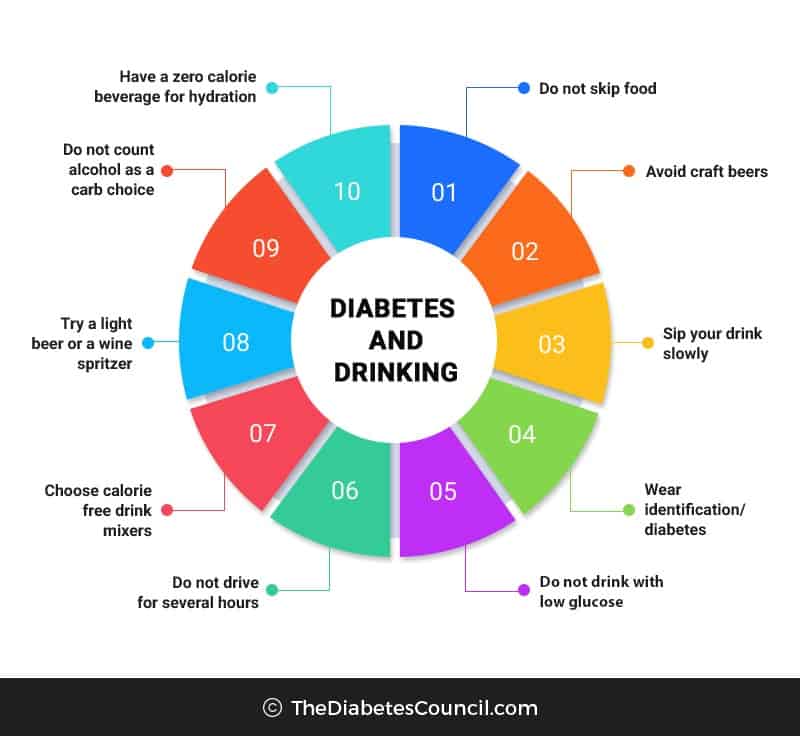

●Drinks excessive alcohol, although even moderate alcohol use can increase the risk of hypoglycemia in people with type 1 diabetes

LOW BLOOD SUGAR SYMPTOMS

The symptoms of low blood sugar vary from person to person, and can change over time. During the early stages low blood sugar, you may:

●Sweat

●Tremble

●Feel hungry

●Feel anxious

If untreated, your symptoms can become more severe, and can include:

●Difficulty walking

●Weakness

●Difficulty seeing clearly

●Bizarre behavior or personality changes

●Confusion

●Unconsciousness or seizure

When possible, you should confirm that you have low blood sugar by measuring your blood sugar level (see "Patient education: Self-monitoring of blood glucose in diabetes mellitus (Beyond the Basics)"). Low blood sugar is generally defined as a blood sugar of 60 mg/dL (3.3 mmol/L) or less.

Some people with diabetes develop symptoms of low blood sugar at slightly higher levels. If your blood sugar levels are high for long periods of time, you may have symptoms and feel poorly when your blood sugar is closer to 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L). Getting your blood sugar under better control can help to lower the blood sugar level when you begin to feel symptoms.

Hypoglycemia unawareness — Hypoglycemia unawareness occurs when you do not have the early symptoms of low blood sugar. As a result, you cannot respond in the early stages, and severe signs of low blood sugar, such as passing out or seizures, are more likely. Being unaware of low blood sugar is a common occurrence, especially in people who have had type 1 diabetes for greater than 5 to 10 years.

Hypoglycemia and hypoglycemia unawareness occur more frequently in people who tightly control their blood sugar levels with insulin (called intensive therapy).

People who drink excessive amounts of alcohol, are tired, or who take a beta blocker (commonly used to control high blood pressure) may not notice their low blood sugar symptoms, or may not recognize that the symptoms are due to low blood sugar.

Hypoglycemia unawareness can also occur in people who take certain oral diabetes medications (eg, glyburide [brand name: Micronase]), especially in older adult people with heart or kidney disease.

Nocturnal hypoglycemia — Low blood sugar that occurs when you are sleeping (nocturnal hypoglycemia) can disrupt sleep but often goes unrecognized. Nocturnal hypoglycemia is a form of hypoglycemia unawareness. Thus, if you have nocturnal hypoglycemia, you are less likely to have symptoms that alert you to the need for treatment. Nocturnal hypoglycemia can be difficult to diagnose, and can increase the risk of hypoglycemia unawareness in the 48 to 72 hours that follow.

LOW BLOOD SUGAR PREVENTION

The best way to prevent low blood sugar is to monitor your blood sugar levels frequently and be prepared to treat it promptly at all times. You and a close friend or relative need to learn the symptoms and should always carry glucose tablets, hard candy, or other sources of fast-acting carbohydrate.

Glucose tablets are recommended since they have a pleasant taste, but you are not likely to eat them unless your blood sugar is low. Candy can be tempting to eat, even when blood sugar levels are normal, especially for children with diabetes.

Low blood sugar can be frightening and unpleasant, and it is common to be fearful of future episodes. This may lead you to keep your blood sugar level high, which can lead to long-term complications.

It may be helpful to discuss fears of low blood sugar with a health care provider. In addition, ask about blood sugar awareness education. Blood sugar awareness training can improve your ability to recognize low blood sugar earlier.

LOW BLOOD SUGAR TREATMENT

When you are low, you should check your blood sugar level as soon as possible. However, go ahead and treat yourself for low blood sugar if your monitoring equipment (blood glucose meter, test strips, lancet) is not readily available. Treat yourself quickly, especially if your blood sugar is less than 40 mg/dL (2.2 mmol/L).

●If your blood sugar is 51 to 70 mg/dL (2.8 to 3.9 mmol/L), eat 10 to 15 grams of fast-acting carbohydrate (eg, 1/2 cup fruit juice, 6 to 8 hard candies, 3 to 4 glucose tablets).

●If you are less than 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L), eat 20 to 30 grams of fast-acting carbohydrates.

This amount of food is usually enough to raise the blood sugar into a safe range without causing high blood sugar levels (called hyperglycemia). Avoid foods that contain fat (like candy bars) or protein (cheese) initially, since they slow down your body's ability to absorb glucose.

Retest after 15 minutes and repeat treatment if needed. If your next meal is more than an hour away, eat an additional 15 grams of carbohydrate and 1 ounce of protein. Examples of this include crackers with cheese or one-half of a sandwich with peanut butter. It is important not to eat too much because this can raise your blood sugar above the target level and lead to weight gain over the long-term.

Glucagon — If your low blood sugar is severe, you may pass out or become too disoriented to eat. A close friend or relative should be trained to recognize severe low blood sugar and treat it quickly. Dealing with a loved one who is pale, sweaty, acting bizarrely, or is passed out and convulsing can be scary. An injection of glucagon stops these symptoms quickly.

Glucagon is a hormone that raises blood glucose levels. Glucagon is available in emergency kits, which can be bought with a prescription in a pharmacy . Directions are included in each kit; a roommate, spouse, or parent should learn how to use the injection before an emergency occurs.

It is important that the glucagon kit is easy to locate, is not expired, and that the friend or relative is able to stay calm. You should refill the kit when the expiration date approaches, although using an expired kit is unlikely to cause harm.

Procedure — Glucagon should be injected in the thigh or abdomen. The injection sites and technique are similar to an insulin injection.

●Remove the needle protector and inject the entire content of the syringe (a clear solution) into the glucagon powder. Do not remove the plastic clip on the syringe. Remove the needle from the bottle.

●Swirl the mixture gently until the powder is dissolved. The solution should be clear. Do not use the solution if it is discolored.

●Hold the bottle upside down and withdraw the contents into the syringe (1 mg mark on syringe for adults and children over 44 pounds [20 kilograms]). Children under 44 pounds need one-half the dose, and only 1/2 the solution should be withdrawn (0.5 mg mark on syringe).

●Choose an injection site in the abdomen or thigh .

●Insert the needle into the skin .

●Press the plunger to inject the glucagon.

●Withdraw the needle, and replace the syringe in the storage case (do not attempt to re-cap the needle). Press lightly at the injection site.

●Turn the person to his or her side. This prevents choking if he/she vomits.

Symptoms should resolve within 10 to 15 minutes, although nausea and vomiting may follow 60 to 90 minutes later. As soon as the person is awake and able to swallow, offer a fast-acting carbohydrate such as glucose tablets or juice. After the person begins to feel better, he or she should eat a snack with protein, such as crackers and cheese or a peanut butter sandwich.

If the patient is not conscious within 10 minutes, another glucagon injection should be given, if a second kit is available. Emergency help should be called immediately.

LOW BLOOD SUGAR FOLLOW-UP CARE

After your blood sugar level normalizes and your symptoms are gone, you can usually resume your normal activities. If you required glucagon, you should call your health care provider. You provider can help you to determine how and why you developed severely low blood sugar, and can suggest adjustments to prevent future reactions.

In the first 48 to 72 hours after a low blood sugar episode, you may have difficulty recognizing the symptoms of low blood sugar. In addition, your body's ability to counteract low blood sugar levels is decreased. Check your blood sugar level before you eat, exercise, or drive to avoid another low blood sugar episode.

WHEN TO SEEK HELP

A family member or friend should take you to the hospital or call for emergency assistance (911 in many United States communities) immediately if you:

●Remain confused 15 minutes after being treated with glucagon

●Are unconscious (or nearly unconscious) and glucagon is not available

●Continue to have low blood sugar despite eating adequate amounts of a fast-acting carbohydrate or receiving glucagon

Once in a hospital or ambulance, you will be given treatment intravenously (IV) to raise your blood sugar level immediately. If you require emergency care, you may be observed in the emergency department for a few hours before being released. A friend or relative should drive you home.

Understanding Hypoglycemia

Most people are aware that keeping blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible helps prevent damage to the blood vessels and nerves in the body. But keeping blood glucose levels near normal can carry some risks as well. People who maintain “tight” blood glucose control are more likely to experience episodes of hypoglycemia, and frequent episodes of hypoglycemia — even mild hypoglycemia and even in people who don’t keep blood glucose levels close to normal — deplete the liver of stored glucose (called glycogen), which is what the body normally draws upon to raise blood glucose levels when they are low. Once liver stores of glycogen are low, severe hypoglycemia is more likely to develop, and research shows that severe hypoglycemia can be harmful. In children, frequent severe hypoglycemia can lead to impairment of intellectual function. In children and adults, severe hypoglycemia can lead to accidents. And in adults with cardiovascular disease, it can lead to strokes and heart attacks.

When you think about diabetes and blood glucose control, the first thing that comes to mind is probably avoiding high blood glucose levels. After all, the hallmark of diabetes is high blood glucose, or hyperglycemia. But controlling blood glucose is more than just managing the “highs”; it also involves preventing and managing the “lows,” or hypoglycemia.

To keep yourself as healthy as possible, you need to learn how to balance food intake, physical activity, and any diabetes medicines or insulin you use to keep your blood glucose as close to normal as is safe for you without going too low. This article explains how hypoglycemia develops and how to treat and prevent it.

What is hypoglycemia?

Blood glucose levels vary throughout the day depending on what you eat, how active you are, and any diabetes medicines or insulin you take. Other things, such as hormone fluctuations, can affect blood glucose levels as well. In people who don’t have diabetes, blood glucose levels generally range from 65 mg/dl to 140 mg/dl, but in diabetes, the body’s natural control is disrupted, and blood glucose levels can go too high or too low. For people with diabetes, a blood glucose level of 70 mg/dl or less is considered low, and treatment is recommended to prevent it from dropping even lower.

Under normal circumstances, glucose is the brain’s sole energy source, making it particularly sensitive to any decrease in blood glucose level. When blood glucose levels drop too low, the body tries to increase the amount of glucose available in the bloodstream by releasing hormones such as glucagon and epinephrine (also called adrenaline) that stimulate the release of glycogen from the liver.

Some of the symptoms of hypoglycemia are caused by the brain’s lack of glucose; other symptoms are caused by the hormones, primarily epinephrine, released to help increase blood glucose levels. Epinephrine can cause feelings of weakness, shakiness, clamminess, and hunger and an increased heart rate. These are often called the “warning signs” of hypoglycemia. Lack of glucose to the brain can cause trouble concentrating, changes in vision, slurred speech, lack of coordination, headaches, dizziness, and drowsiness. Hypoglycemia can also cause changes in emotions and mood. Feelings of nervousness and irritability, becoming argumentative, showing aggression, and crying are common, although some people experience euphoria and giddiness. Recognizing emotional changes that may signal hypoglycemia is especially important in young children, who may not be able to understand or communicate other symptoms of hypoglycemia to adults. If hypoglycemia is not promptly treated with a form of sugar or glucose to bring blood glucose level up, the brain can become dangerously depleted of glucose, potentially causing severe confusion, seizures, and loss of consciousness.

Who is at risk?

Some people are at higher risk of developing hypoglycemia than others. Hypoglycemia is not a concern for people who manage their diabetes with only exercise and a meal plan. People who use insulin or certain types of oral diabetes medicines have a much greater chance of developing hypoglycemia and therefore need to be more careful to avoid it. Other risk factors for hypoglycemia include the following:

- Maintaining very “tight” (near-normal) blood glucose targets.

- Decreased kidney function. The kidneys help to degrade and remove insulin from the bloodstream. When the kidneys are not functioning well, insulin action can be unpredictable, and low blood glucose levels may result.

- Alcohol use.

- Conditions such as gastropathy (slowed stomach emptying) that cause variable rates of digestion and absorption of food.

- Having autonomic neuropathy, which can decrease symptoms when blood glucose levels drop. (Autonomic neuropathy is damage to nerves that control involuntary functions.)

- Pregnancy in women with preexisting diabetes, especially during the first trimester.

A side effect of diabetes treatment

Hypoglycemia is the most common side effect of insulin use and of some of the oral medicines used to treat Type 2 diabetes. How likely a drug is to cause hypoglycemia and the appropriate treatment for hypoglycemia depends on the type of drug.

Secretagogues. Oral medicines that stimulate the pancreas to release more insulin, which include sulfonylureas and the drugs nateglinide (brand name Starlix) and repaglinide (Prandin), have the potential side effect of hypoglycemia. Sulfonylureas include glimepiride (Amaryl), glipizide (Glucotrol and Glucotrol XL), and glyburide (DiaBeta, Micronase, and Glynase).

Sulfonylureas are taken once or twice a day, in the morning and the evening, and their blood-glucose-lowering effects last all day. If you miss a meal or snack, the medicine continues to work, and your blood glucose level may drop too low. So-called sulfa antibiotics (those that contain the ingredient sulfamethoxazole) can also increase the risk of hypoglycemia when taken with a sulfonylurea. Anyone who takes a sulfonylurea, therefore, should discuss this potential drug interaction with their health-care provider should antibiotic therapy be necessary.

Nateglinide and repaglinide are taken with meals and act for only a short time. The risk of hypoglycemia is lower than for sulfonylureas, but it is still possible to develop hypoglycemia if a dose of nateglinide or repaglinide is taken without food.

Insulin. All people with Type 1 diabetes and many with Type 2 use insulin for blood glucose control. Since insulin can cause hypoglycemia, it is important for those who use it to understand how it works and when its activity is greatest so they can properly balance food and activity and take precautions to avoid hypoglycemia. This is best discussed with a health-care provider who is knowledgeable about you, your lifestyle, and the particular insulin regimen you are using.

Biguanides and thiazolidinediones. The biguanides, of which metformin is the only one approved in the United States, decrease the amount of glucose manufactured by the liver. The thiazolidinediones, pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia), help body cells become more sensitive to insulin. The risk of hypoglycemia is very low with these medicines. However, if you take metformin, pioglitazone, or rosiglitazone along with either insulin or a secretagogue, hypoglycemia is a possibility.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. Drugs in this class, acarbose (Precose) and miglitol (Glyset), interfere with the digestion of carbohydrates to glucose and help to lower blood glucose levels after meals. When taken alone, these medicines do not cause hypoglycemia, but if combined with either insulin or a secretagogue, hypoglycemia is possible. Because alpha-glucosidase inhibitors interfere with the digestion of some types of carbohydrate, hypoglycemia can only be treated with pure glucose (also called dextrose or d-glucose), which is sold in tablets and tubes of gel. Other carbohydrates will not raise blood glucose levels quickly enough to treat hypoglycemia.

DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors. When taken alone, DPP-4 inhibitors, such as sitagliptin (Januvia), saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and alogliptin (Nesina); GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as exenatide (Byetta and Bydureon), liraglutide (Victoza), albiglutide (Tanzeum), and dulaglutide (Trulicity); and SGLT2 inhibitors, such as canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and empagliflozin (Jardiance) do not usually cause hypoglycemia. However, lows can occur when drugs in these classes are combined with a therapy that can cause hypoglycemia, such as insulin or sulfonylureas.

Striking a balance

Although hypoglycemia is called a side effect of some of the drugs used to lower blood glucose levels, it would be more accurate to call it a potential side effect of diabetes treatment — which includes food and activity as well as drug treatment. When there is a disruption in the balance of these different components of diabetes treatment, hypoglycemia can result. The following are some examples of how that balance commonly gets disrupted:

Skipping or delaying a meal. When you take insulin or a drug that increases the amount of insulin in your system, not eating enough food at the times the insulin or drug is working can cause hypoglycemia. Learning to balance food with insulin or oral drugs is key to achieving optimal blood glucose control while avoiding hypoglycemia.

Too much diabetes medicine. If you take more than your prescribed dose of insulin or a secretagogue, there can be too much insulin circulating in your bloodstream, and hypoglycemia can occur. Changes in the timing of insulin or oral medicines can also cause hypoglycemia if your medicine and food plan are no longer properly matched.

Increase in physical activity. Physical activity and exercise lower blood glucose level by increasing insulin sensitivity. This is generally beneficial in blood glucose control, but it can increase the risk of hypoglycemia in people who use insulin or secretagogues if the exercise is very vigorous, carbohydrate intake too low, or the activity takes place at the time when the insulin or secretagogue has the greatest (peak) action. Exercise-related hypoglycemia can occur as much as 24 hours after the activity.

Increase in rate of insulin absorption. This may occur if the temperature of the skin increases due to exposure to hot water or the sun. Also, if insulin is injected into a muscle that is used in exercise soon after (such as injecting your thigh area, then jogging), the rate of absorption may increase.

Alcohol. Consuming alcohol can cause hypoglycemia in people who take insulin or a secretagogue. When the liver is metabolizing alcohol, it is less able to break down glycogen to make glucose when blood glucose levels drop. In addition to causing hypoglycemia, this can increase the severity of hypoglycemia. Alcohol can also contribute to hypoglycemia by reducing appetite and impairing thinking and judgment.

Hypoglycemia unawareness

Being able to recognize hypoglycemia promptly is very important because it allows you to take steps to raise your blood glucose as quickly as possible. However, some people with diabetes don’t sense or don’t experience the early warning signs of hypoglycemia such as weakness, shakiness, clamminess, hunger, and an increase in heart rate. This is called hypoglycemia unawareness. Without these early warnings and prompt treatment, hypoglycemia can progress to confusion, which can impair your thinking and ability to treat the hypoglycemia.

If the goals you have set for your personal blood glucose control are “tight” and you are having frequent episodes of hypoglycemia, your brain may feel comfortable with these low levels and not respond with the typical warning signs. Frequent episodes of hypoglycemia can further blunt your body’s response to low blood glucose. Some drugs, such as beta-blockers (taken for high blood pressure), can also mask the symptoms of hypoglycemia.

If you have hypoglycemia frequently, you may need to raise your blood glucose targets, and you should monitor your blood glucose level more frequently and avoid alcohol. You may also need to adjust your diabetes medicines or insulin doses. Talk to your diabetes care team if you experience several episodes of hypoglycemia a week, have hypoglycemia during the night, have such low blood glucose that you require help from someone else to treat it, or find you are frequently eating snacks that you don’t want simply to avoid low blood glucose.

Treating lows

Anyone at risk for hypoglycemia should know how to treat it and be prepared to do so at any time. Here’s what to do: If you recognize symptoms of hypoglycemia, check your blood glucose level with your meter to make sure. While the symptoms are useful, the numbers are facts, and other situations, such as panic attacks or heart problems, can lead to similar symptoms. In some cases, people who have had chronically high blood glucose levels may experience symptoms of hypoglycemia when their blood glucose level drops to a more normal range. The usual recommendation is not to treat normal or goal-range blood glucose levels, even if symptoms are present.

Treatment is usually recommended for blood glucose levels of 70 mg/dl or less. However, this may vary among individuals. For example, blood glucose goals are lower in women with diabetes who are pregnant, so they may be advised to treat for hypoglycemia at a level below 70 mg/dl. People who have hypoglycemia unawareness, are elderly, or live alone may be advised to treat at a blood glucose level somewhat higher than 70 mg/dl. Young children are often given slightly higher targets for treating hypoglycemia for safety reasons. Work with your diabetes care team to devise a plan for treating hypoglycemia that is right for you.

To treat hypoglycemia, follow the “rule of 15”: Check your blood glucose level with your meter, treat a blood glucose level under 70 mg/dl by consuming 15 grams of carbohydrate, wait about 15 minutes, then recheck your blood glucose level with your meter. If your blood glucose is still low (below 80 mg/dl), consume another 15 grams of carbohydrate and recheck 15 minutes later. You may need a small snack if your next planned meal is more than an hour away. Since blood glucose levels may begin to drop again about 40–60 minutes after treatment, it may be a good idea to recheck your blood glucose level approximately an hour after treating a low to determine if additional carbohydrate is needed.

The following items have about 15 grams of carbohydrate:

- 3–4 glucose tablets

- 1 dose of glucose gel (in most cases, 1 small tube is 1 dose)

- 1/2 cup of orange juice or regular soda (not sugar-free)

- 1 tablespoon of honey or syrup

- 1 tablespoon of sugar or 5 small sugar cubes

- 6–8 LifeSavers

- 8 ounces of skim (nonfat) milk

If these choices are not available, use any carbohydrate that is — for example, bread, crackers, grapes, etc. The form of carbohydrate is not important; treating the low blood glucose is. (However, many people find they are less likely to overtreat low blood glucose if they consistently treat lows with a more “medicinal” form of carbohydrate such as glucose tablets or gel.)

If you take insulin or a secretagogue and are also taking an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor (acarbose or miglitol), carbohydrate digestion and absorption is decreased, and the recommended treatment is glucose tablets or glucose gel.

Other nutrients in food such as fat or resistant starch (which is present in some diabetes snack bars) can delay glucose digestion and absorption, so foods containing these ingredients are not good choices for treating hypoglycemia.

If hypoglycemia becomes severe and a person is confused, convulsing, or unconscious, treatment options include intravenous glucose administered by medical personnel or glucagon by injection given by someone trained in its use and familiar with the recipient’s diabetes history. Glucagon is a hormone that is normally produced by the pancreas and that causes the liver to release glucose into the bloodstream, raising the blood glucose level. It comes in a kit that can be used in an emergency situation (such as when a person is unable to swallow a source of glucose by mouth). The hormone is injected much like an insulin injection, usually in an area of fatty tissue, such as the stomach or back of the arms. Special precautions are necessary to ensure that the injection is given correctly and that the person receiving the injection is positioned properly prior to receiving the drug. People at higher risk of developing hypoglycemia should discuss the use of glucagon with their diabetes educator, doctor, or pharmacist.

Avoiding hypoglycemia

Avoiding all episodes of hypoglycemia may be impossible for many people, especially since maintaining tight blood glucose control brings with it a higher risk of hypoglycemia. However, the following tips may help to prevent excessive lows:

- Know how your medicines work and when they have their strongest action.

- Work with your diabetes care team to coordinate your medicines or insulin with your eating plan. Meals and snacks should be timed to coordinate with the activity of your medicine or insulin.

- Learn how to count carbohydrates so you can keep your carbohydrate intake consistent at meals and snacks from day to day. Variations in carbohydrate intake can lead to hypoglycemia.

- Have carbohydrate-containing foods available in the places you frequent, such as in your car or at the office, to avoid delays in treatment of hypoglycemia.

- Develop a plan with your diabetes care team to adjust your food, medicine, or insulin for changes in activity or exercise.

- Discuss how to handle sick days and situations where you have trouble eating with your diabetes team.

- Always check your blood glucose level to verify any symptoms of hypoglycemia. Keep your meter with you, especially in situations where risk of hypoglycemia is increased.

- Wear a medical alert identification tag.

- Always treat blood glucose levels of 70 mg/dl or less whether or not you have symptoms.

- If you have symptoms of hypoglycemia and do not have your blood glucose meter available, treatment is recommended.

- If you have hypoglycemia unawareness, you may need to work with your diabetes care team to modify your blood glucose goals or treatment plan.

- Check your blood glucose level frequently during the day and possibly at night, especially if you have hypoglycemia unawareness, are pregnant, or have exercised vigorously within the past 24 hours.

- Check your blood glucose level before driving or operating machinery to avoid any situations that could become dangerous if hypoglycemia occurred.

- Check the expiration date on your glucagon emergency kit once a year and replace it before it expires.

- Discuss alcohol intake with your diabetes care team. You may be advised not to drink on an empty stomach and/or to increase your carbohydrate intake if alcohol is an option for you. If you drink, always check your blood glucose level before bed and eat any snacks that are scheduled in your food plan.

Don’t risk your health

Although hypoglycemia can, at times, be unpleasant, don’t risk your health by allowing your blood glucose levels to run higher than recommended to avoid it. Meet with your diabetes care team to develop a plan to help you achieve the best possible blood glucose control safely and effectively. Think positive, and learn to be prepared with measures to prevent and promptly treat hypoglycemia should it occur.

0 comments: